New Import GST on Goods Valued Under $1000: the What & How

25-minute read

The government is cutting import taxes on low-value goods to soften the impact for New Zealand consumers who start paying GST on all overseas purchases next year.

Following consultation earlier in 2018, details were released on 18 October 2018 on the proposed GST regime for non-residents supplying “low-value goods” to NZ buyers.

While many aspects of the proposals remain the same as originally proposed, a major change is the proposal to apply the rules to all consignments of goods costing NZD 1,000 or less (as compared to the originally proposed threshold of NZD 400).

The policy is in line with Australia, which has registered 700 overseas suppliers for GST and follows the European Union’s approach to sales tax.

The government has been successfully collecting GST on overseas digital services and products, such as movies and software since 2016.

While the legislation will not be introduced into Parliament until November 2018, there is still a commitment to have the regime apply from 1 October 2019.

The new rules will apply to offshore suppliers that make supplies (or expect to make supplies) of goods to New Zealand consumers of NZD 60,000 or more in a 12-month period.

Electronic marketplaces and “re-deliverers” also will have a requirement to register and comply with the new rules.

Low-value goods will be defined as imports with a consignment value of NZD 1,000 or less. New Zealand tariffs and cost recovery charges will no longer apply to supplies covered by the new rules (alcohol, tobacco and fine metals are excluded from these rules).

Under the current GST rules , all sales by non-residents of goods on which the total amount of GST and duty is less than NZD 60 per shipment are not subject to GST at the border, and no GST is due on the sale.

Due to varying rates of duty on goods, there is no single value on which GST does not apply, in some cases it is under NZD 400, and in other cases only goods under around NZD 230 are not subject to GST currently.

The new rules will do away with this distinction and simply focus on whether the consignment value is NZD 1,000 or less.

How will a supplier know if a customer is a New Zealand consumer?

Suppliers will need to charge GST if the destination of the goods is a delivery address in New Zealand.

Offshore suppliers will not be required to return GST on supplies to New Zealand GST-registered businesses. There will be an optional rule allowing offshore suppliers to zero-rate supplies to New Zealand GST-registered businesses.

This approach would allow any GST incurred by the offshore supplier to be claimed back (for example costs of attending trade fairs in New Zealand). If supplies to businesses are zero-rated, these are included when calculating whether the NZD 60,000 registration threshold is exceeded.

Offshore suppliers will be able to presume that a New Zealand resident customer is not a GST-registered business unless the customer has provided its GST registration number, New Zealand Business Number or otherwise notified the supplier of its GST-registered status.

If offshore suppliers are making supplies of types of goods that typically are consumed only by businesses, we expect it will be possible to seek agreement from Inland Revenue that it can be presumed all customers are GST-registered businesses.

This rule already exists for the existing remote services rules.

Marketplaces

When certain conditions are satisfied, an operator of an online marketplace (whether based in New Zealand or offshore) may be required to register and return GST on supplies made through the marketplace by non-resident suppliers, instead of the underlying supplier.

It is proposed that a marketplace would be liable to account for GST unless it does not authorise payment, authorise the delivery or directly or indirectly set any of the terms or conditions of the supply. These rules are consistent with the approach adopted in Australia.

If a marketplace does not process the payment for a supply of goods, in some instances the marketplace will be able to claim a bad debt deduction if it is unable to collect the GST and any other fees from the supplier.

A marketplace will be subject to the NZD 60,000 registration threshold; however, this will include the total value of both low-value goods and remote services.

Re-deliverers

Catering to the needs of New Zealand consumers that want to purchase from retailers that will not ship to New Zealand, there is now a range of businesses that create local delivery addresses and then ship the goods to New Zealand. There are also personal shopping services available.

These businesses will be liable to register for GST and will need to collect the 15% GST on the value of the goods (the information released does not specify whether GST also must be charged on the redelivery services that take place outside New Zealand).

A re-deliverer will need to register when the value of the goods it “re-delivers” exceeds NZD 60,000 in a 12-month period.

Supplies above NZD 1,000

Where the value of a consignment of goods exceeds NZD 1,000, the current rules will continue to apply, and rather than the supplier charging GST, GST (and any applicable duty) will be collected at the New Zealand border, with the purchaser unable to collect its goods until the tax is paid.

Suppliers will, in some instances, be able to charge GST on goods costing more than NZD 1,000 (these rules also will apply to marketplaces and re-deliverers).

Compliance requirements

While not covered in the proposals released on 18 October, we expect that suppliers that are required to register under these rules will be able to apply for a simplified “pay-only” registration basis, or may undertake a full registration allowing them to claim back any New Zealand GST incurred in making New Zealand sales.

Offshore suppliers that are already GST registered under the remote services rules do not need to separately re-register for these new proposed rules.

GST returns ordinarily will be due in quarterly instalments (March, June, September, and December). There will be an optional one-off six-month filing period from 1 October 2019-31 March 2020 to allow suppliers to adapt to the new filing requirements.

The New Zealand government will be monitoring compliance with the rules, including through sharing of information between New Zealand Customs and Inland Revenue and using powers under double tax agreements to obtain information about foreign taxpayers.

Summary of the proposals

From 1 October 2019:

- Offshore suppliers would be required to register, collect, and return New Zealand GST on goods valued at or below $1,000 supplied to consumers in New Zealand.

- The rules would apply when the good is outside New Zealand at the time of supply and is delivered to a New Zealand address.

- Offshore suppliers would be required to register when their total taxable supplies of goods and services to New Zealand exceed $60,000 in a 12-month period. In certain circumstances, marketplaces and re-deliverers may also be required to register.

- Tariffs and border cost recovery charges would be removed from imported consignments valued at or below $1,000.

- The current processes for collecting GST and other duty at the border by Customs would continue to apply for consignments valued over $1,000. However, there will be processes put in place so Customs does not collect GST on goods in a consignment over $1,000 if GST was already collected by the supplier.

- The current border processes for managing risks in relation to imported goods, including biosecurity assessment, will remain in place.

QUESTIONS & ANSWERS

Q1. Is this a new tax?

New Zealand has a broad-based GST that has always applied to goods imported for consumption. The reason for not collecting GST on imported low-value goods has been that the costs of the collection at the border made it impractical to do so.

The growth in online shopping from offshore retailers and the advances in technology mean that collecting GST at the point of sale is now more efficient. It is estimated that the foregone revenue from not collecting GST on low-value imported goods is growing at twelve percent a year and this is not sustainable.

Q2. Why is this issue a priority for the Government?

It’s a question of fairness. New Zealand’s GST is a broad-based consumption tax with few exemptions. It’s based on the principle that goods and services are subject to GST when they are consumed in New Zealand.

Unlike offshore suppliers, domestic retailers currently have GST added to the price tag of their goods, they collect GST, and pay it to Inland Revenue. So the proposed measures will help to restore some balance.

Q3. These goods aren’t made or sold in New Zealand so why should they be subject to GST?

Your phone is not made in New Zealand either, but you pay GST on that.

GST is a tax on consumption − the consumer pays the tax and it makes no difference where the item was manufactured. New Zealand’s GST, like most GST/VAT systems around the world, operates on the principle that goods and services should be taxed in the jurisdiction in which they are consumed.

Therefore, imported goods should have GST collected on them. The only reason they don’t currently is because when GST was introduced in 1986, few New Zealand consumers imported goods and if they did, it tended to be higher value items.

At that time, the compliance and administrative costs that would have been involved in collecting tax on imported low-value goods outweighed the potential revenue.

The growth of online shopping means the volume of goods purchased offshore for consumption in New Zealand on which GST has not been collected is increasingly significant.

$870 million was spent online in 2017/18 on goods below $400 from offshore suppliers and the value of this spending is growing at around twelve percent a year.

Q4. Why weren’t other options considered for collecting GST on low-value imported goods?

The offshore registration model is the most efficient collection mechanism at this time given the limitations of other approaches. The Tax Working Group was asked to look at this issue and they recommended that the Government implement an offshore supplier registration system for collecting GST on low-value imported goods.

The Tax Working Group concluded that other options for collecting GST on low-value imported goods are not feasible at the present time. This view is backed up by other jurisdictions, such as Australia, Switzerland, and the EU member states that have either implemented or committed to implement offshore supplier registration.

Consistency with the approaches of these other countries can realise benefits for New Zealand in terms of encouraging voluntary compliance by offshore suppliers.

Following the international best practice, including simplified rules that are consistent with other countries’ systems, makes sense as it would ensure that the rules are familiar and relatively simple for offshore suppliers to comply with.

While other collection models were suggested during the consultation process, the Government still agrees with the Tax Working Group’s recommendation that an offshore supplier registration system is the most feasible model at the present time.

However, as noted by the Tax Working Group, the Government does not rule out alternative options for collecting GST on low-value goods as and when developments in technology allow.

Q5. What do other countries do?

While the issue of the non-collection of GST on low-value imported goods is not unique to New Zealand, unlike imported services and digital products, there are no common guidelines in relation to GST on imported goods.

Nevertheless, there have been some developments internationally. Most notably in Australia where, from 1 July 2018, an offshore supplier registration system has been used for collecting GST on low-value imported goods.

Australia’s approach underwent a Senate inquiry and a review by the Australian Productivity Commission. The Australian Productivity Commission concluded the offshore supplier registration system was the best approach given the available technology.

Australia has had over 700 registrations after one month of the rules being in force.

The European Union has committed to an offshore supplier registration system for collecting Value Added Tax (VAT) on imported goods from sellers outside the EU. The EU’s new rules will take effect from 1 January 2021.

Switzerland will also introduce an offshore supplier registration system from 1 January 2019 for the collection of VAT on both imported services and low-value goods.

Q6. Why is a $1,000 threshold preferable to a $400 threshold?

Following consultation a number of things became clearer:

- A higher threshold would make it easier for suppliers to comply because there is less likely they would have to work out whether or not goods are above or below the threshold. If all the goods they sell are below $1,000 they can simply add GST to everything they sell.

- There is also less risk that goods will be taxed twice (or not at all) because much fewer consignments imported are likely to be valued near or above the $1,000 threshold compared with the lower $400 threshold.

- A $1,000 threshold would result in a better experience for consumers as fewer goods would be stopped at the border for revenue collection, particularly those sent by post. With a $400 threshold, New Zealand Post would stop and hold everything above $400 until the consumer pays Customs.

- Having suppliers collect GST on goods in a wider value range may also provide greater price transparency for consumers, as offshore websites may be more likely to display a GST-inclusive price for all of their goods. Retail banking data suggests there were 230,000 purchases by New Zealand consumers of imported goods between $400 and $1,000 in 2017/18, compared with just 57,000 transactions between $1,000 and $2,000.

Q7. If suppliers find it easier to charge GST on all their supplies of goods to consumers in New Zealand, including goods over $1,000, can they choose to do so?

In certain circumstances, offshore suppliers, marketplaces and re-deliverers would be able to charge GST on goods above $1,000 supplied to New Zealand consumers.

If only five percent or less of the total value of sales of goods to consumers in New Zealand is of goods valued over $1,000, the supplier would be able to elect to charge GST on these goods.

Suppliers that do not meet this test would be able to apply to the Commissioner of Inland Revenue to also be allowed to charge GST on their supplies of high-value goods.

The Commissioner would consider a number of factors in deciding whether to allow a supplier that doesn’t meet the five percent test to charge GST on their high-value goods.

Suppliers that elect to charge GST on their supplies of high-value goods would need to notify Inland Revenue that they are doing so. Marketplaces that elect to charge GST on their supplies of high-value goods would also need to notify their underlying suppliers.

Q8. What is the joint and several liability approach adopted by the United Kingdom?

The United Kingdom introduced legislation to make electronic marketplaces jointly and severally liable for any future unpaid VAT of both United Kingdom and non-United Kingdom businesses arising from sales of goods in the United Kingdom through that marketplace.

The measure was aimed at tackling VAT fraud and errors by online sellers of goods.

In addition to the new legislation, the United Kingdom government has published an agreement online that electronic marketplaces can sign up to. The agreement is intended to facilitate cooperation between HM Revenue and Customs and electronic marketplaces to promote VAT compliance by online sellers using these marketplaces.

The joint and several liability approaches to collecting GST/VAT from offshore suppliers requires the tax authority to:

- register and monitor the compliance of thousands of suppliers selling through each marketplace;

- open investigations where non-compliance has been detected (the United Kingdom has opened over 3,000 cases to date); and

- request the marketplace guarantee future compliance from the supplier on their website or remove them.

If New Zealand was to take the same approach, the overall costs of collecting GST would be higher, the underlying suppliers would incur the bulk of the compliance costs and might choose to stop selling to New Zealand.

FISCAL IMPLICATIONS

Q9. How much is the proposed system expected to cost the Government?

Final costs of the proposed system are yet to be determined, but given our experience with offshore supplier registration for cross-border services, we do not expect the costs to be significant.

Q10. How much GST revenue is the proposed offshore supplier registration system expected to collect?

In Budget 2018 it was estimated that implementing an offshore supplier registration system for collecting GST on imported goods valued at or below $400 would result in an additional $218 million in GST revenue over the forecast period (2019/20 to 2021/22).

The forgone revenue estimate for the 2017/18 year was $130 million.

Using more accurate and recent data, it is now estimated that an offshore supplier registration system for collecting GST on goods valued at or below $1,000 would result in an additional $60 million in GST revenue over the forecast period compared with the Budget 2018 estimates.

We conservatively estimate that $278 million would be collected over the 2019/20 to 2021/22 forecast period, broken down as follows:

2019/20 $66m

2020/21 $100m

2021/22 $112m

Q11. What is the rate of compliance that has been assumed in coming up with these estimates?

The revenue estimates are based on an assumption that seventy five percent of the GST that would be collected if all liable suppliers registered and complied with the rules will actually be collected.

Liable suppliers include offshore suppliers selling more than NZ$60,000 in total annual sales to New Zealand consumers, as well as marketplaces and re-deliverers that are deemed to supply more than $60,000 of low-value imported goods to New Zealand consumers annually.

Q12. Retail NZ’s estimate of the forgone GST revenue is $235 million, which they expect to increase to $935 million within nine years. Why do you think Retail NZ and officials’ estimates vary so vastly?

Estimating the total forgone revenue on imported low-value goods relies on data and a number of assumptions. Different data sets and assumptions were used by officials and by Retail NZ so the estimates will naturally vary too.

IMPLICATIONS FOR CONSUMERS

Q13. How will the proposed changes affect consumers?

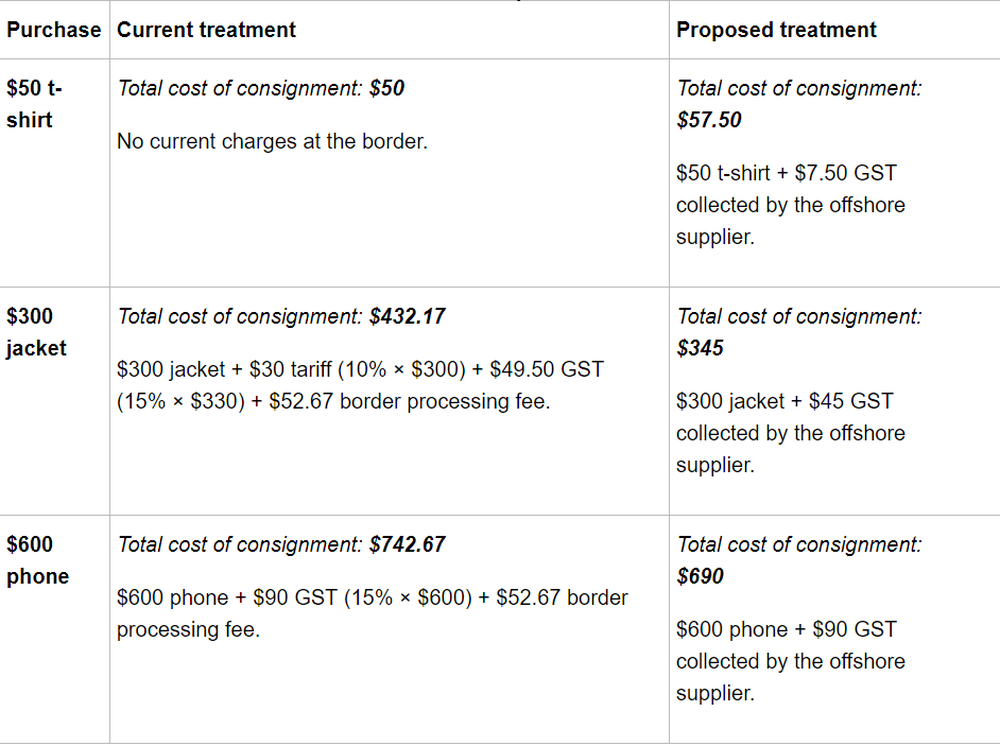

Under the proposal, GST would be charged at the point of sale by the supplier or marketplace when the value of the goods is $1,000 or less. Consumers will pay a little more for most goods valued at less than $400 because they will be charged GST.

You would pay less for goods valued between $400 and $1,000 because tariffs and cost recovery charges for imported consignments between $400 and $1,000 will be removed. Imported consignments over $1,000 will still have tariffs and cost recovery charges collected on them at the border.

There will also be greater transparency for consumers who would less often be surprised and inconvenienced by having to pay additional GST, tariffs and cost recovery charges once their purchases reach the border. What they pay online would be the actual price.

Example

Q14. Will goods be held up at the border as a result of the proposals?

No. Consignments valued at or under $1,000 will not be stopped at the border for revenue collection purposes − the current process for collecting GST and tariff duty at the border on consignments over $1,000 will continue to apply.

However, there will be processes put in place to ensure Customs does not collect GST on goods in a consignment over $1,000 if the supplier has already charged GST.

Setting the threshold at $1,000 may be beneficial for fast freight carriers, customs brokers and New Zealand Post with fewer goods stopped at the border for revenue collection. This may reduce costs for these border agents and mitigate some of the risks with the anticipated rapid growth in import volumes.

Q15. How will consumers be able to get a refund of GST if they return a good?

If you return a purchase to an offshore supplier, the supplier would be responsible for refunding the GST to you.

Q16. What cost recovery charges are currently collected by Customs and the Ministry for Primary Industries on imported consignments? How much funding will be forgone by not collecting these charges on imported consignments valued at or below $1,000?

Customs charges an Import Entry Transaction Fee of $29.26 and the Ministry for Primary Industries charges a $23.41 Biosecurity System Entry Levy on goods that require an import entry. This totals $52.67 inclusive of GST.

Cost recovery charges are used to fund Customs’ and the Ministry for Primary Industries’ risk and biosecurity activities at the border. Under the proposals the Import Entry Transaction Fee and associated Biosecurity System Entry Levy would be forgone on consignments valued at or below $1,000.

In the 2017/18 year Customs and the Ministry for Primary Industries collected $17.80 million in cost recovery charges on consignments below $1,000 which would be forgone under the proposal.

Q17. What tariffs will be forgone under the proposals?

Under the proposed offshore supplier registration system, tariffs would not be collected on imported consignments valued at or below $1,000. Based on the 2017/18 year, this would result in $3.23 million in tariff revenue being forgone.

However, the amount of forgone tariff revenue is likely to decrease over time owing to the implementation of New Zealand’s current and future free trade agreements. Forgoing tariffs is not expected to have a significant impact on New Zealand’s “negotiating coin” in free trade agreement negotiations with trade partners.

Q18. Does a $1,000 threshold create a risk to border and biosecurity risk management?

Currently, importers are required to provide information to support effective and efficient risk management, such as tariff codes, product descriptions and other information to enable the identification of the origin of the goods. This will not change.

There are existing penalties for the provision of incorrect information which is also not proposed to change.

IMPLICATIONS FOR OFFSHORE SUPPLIERS

Q19. Would all offshore suppliers of low-value imported goods be required to register for GST?

Offshore suppliers would be required to register and return GST if their total supplies in a 12-month period to New Zealand consumers exceed NZ$60,000. This is the same threshold that applies to domestic businesses and to offshore suppliers of cross-border services.

Q20. Will offshore suppliers be required to collect GST on goods supplied to GST registered businesses?

No. Supplies to GST-registered New Zealand businesses are excluded from the proposed rules. However, offshore suppliers would be able to choose to zero-rate their supplies of low-value goods to GST-registered businesses (that is, charge GST at the rate of zero percent).

This would allow offshore suppliers to claim a deduction for any New Zealand GST they incur on their inputs into making supplies of low-value goods to GST-registered businesses.

Q21. Why have supplies to GST-registered businesses been excluded from the proposed rules?

Applying the proposed rules to supplies made to GST-registered businesses could create a revenue risk for the Government.

If offshore suppliers charged GST to a GST-registered business but did not return it to Inland Revenue, the Government could lose money as GST-registered businesses are entitled to claim back from Inland Revenue the GST they have paid on their purchases.

Supplies to GST-registered businesses were also excluded from the rules applying GST to cross-border services for the same reason.

Q22. Are there any other exceptions?

Offshore suppliers would not return GST on supplies of fine metal and of alcohol and tobacco products. Supplies of fine metal are already exempt from GST under existing rules.

GST is already collected on all imported alcohol and tobacco products at the border by Customs along with excise taxes and any other applicable charges, regardless of the value of these goods. There is no proposal to change this.

Q23. Could having suppliers collect GST on imported goods valued at or below $1,000 and Customs collect GST on imported consignments over $1,000 result in double taxation? What will suppliers need to do to prevent double taxation?

Double taxation could potentially arise in a number of ways. Firstly exchange rate fluctuations between the time of supply and the time of importation could result in a supplier valuing a good at or below $1,000 and Customs valuing the good above $1,000.

Secondly, multiple low-value goods could be sent together in a single consignment valued over $1,000, for example: three $400 goods shipped together in a single package.

Thirdly, a low-value good could be shipped in a consignment with a high-value good, for example: a $50 helmet could be shipped together with a $1,200 bicycle. Finally, double taxation could arise when suppliers have exercised the option to charge GST on their supplies of high-value goods.

To prevent double taxation, Customs will not collect GST on a good in a consignment over $1,000 if the supplier has already collected GST and Customs is notified of this in the import documentation.

To assist in preventing double taxation, suppliers would be required to take reasonable steps to include the relevant tax information on Customs documents. Suppliers would also be required to provide consumers with a receipt that can be shown to Customs to prevent double taxation.

If double taxation still occurs, the supplier would be required to refund the GST they collected to the consumer.

Q24. What valuation methodology will suppliers need to use for determining if a good is above or below the $1,000 threshold?

In determining whether or not an imported consignment is above or below the $1,000 threshold, Customs will calculate the “customs value” of the consignment.

The customs value is generally the transaction value of the goods with deductions made for the costs of transportation, insurance and other charges and expenses related to the handling and transportation of the goods from the time they have left the country of export.

For the purposes of determining whether GST applies at the point of sale, a supplier would be able to self-assess the customs value using a reasonable estimate as at the time of supply.

This estimate would generally be based on the price paid or payable for the goods, excluding any amounts included in the price for transport, insurance and Customs duties or other taxes payable in New Zealand, including GST.

If the reasonable estimate of the Customs value of a good is $1,000 or less the supplier must charge GST. The amount charged by the supplier for transport, insurance and other services related to the supply of the goods will be added back in to the value of the supply for calculating the amount of GST payable.

Suppliers selling goods in a foreign currency will need to determine the goods’ value in New Zealand dollars at the time of supply in order to determine if they need to charge GST.

However, the goods do not need to be priced in New Zealand dollars, and there will be a range of options for suppliers to use the exchange rate at the time of supply or the applicable exchange rate at another time (such as the time of filing the GST return) when converting foreign currency amounts to determine the amount of GST required to be returned in New Zealand dollars.

Q25. How often will offshore suppliers be required to file GST returns?

Offshore suppliers would be required to file GST returns on a quarterly basis. This is consistent with the rules for non-resident suppliers of remote services.

However, offshore suppliers will be able to elect to have a six month taxable period for the first six months of the rules. This will give these suppliers an extra three months until they have to file their first return. From 1 April 2020 all offshore suppliers will have to use quarterly filing periods.

ELECTRONIC MARKETPLACES AND RE-DELIVERERS

Q26. What is an electronic marketplace and when would they be required to register?

An electronic marketplace is an online platform, such as a website or internet portal, that is used by suppliers to market and sell their goods and services.

In situations where an offshore supplier sells their goods through a marketplace, the marketplace would be required to register and return the GST on the goods instead of the supplier. The rules for electronic marketplaces would apply equally to both resident and non-resident marketplaces.

The $60,000 GST registration threshold would apply to a marketplace rather than its underlying suppliers.

A marketplace would therefore be required to register and return GST in cases where the total value of remote services and low-value goods supplied to New Zealand consumers through the marketplace exceeds $60,000 in a 12-month period.

Offshore suppliers who only supply their goods to New Zealand customers through a marketplace would not be required to register – the marketplace would instead be required to register and return GST on those supplies.

However, the underlying offshore supplier may be required to register if they do not make all of their supplies of goods and services through a marketplace, and the total value of goods and services supplied to New Zealand consumers (but not sold through a marketplace) in a 12-month period is above the $60,000 registration threshold.

Q27. What is a re-deliverer and when would they be required to register?

Re-deliverers are used by consumers when the supplier or marketplace does not offer shipping to New Zealand. The item is instead shipped to an overseas “hub” or mailbox, and then shipped to New Zealand by the re-deliverer. Personal shoppers will also be covered by the rules for re-deliverers.

In situations in which a re-deliverer is used, the marketplace or supplier is unlikely to know that the goods will be sent to New Zealand. However, re-deliverers will know the final destination of the goods they are “redelivering”.

Under the proposals, re-deliverers would be required to register and return GST if the total value of the goods that they “re-deliver” to New Zealand consumers exceeds $60,000 in a 12-month period.

Q28. Are the marketplaces expected to comply?

The major marketplaces are complying in Australia. However, since New Zealand is a smaller market than Australia there is always a risk that a marketplace may decide to withdraw from New Zealand. To date none of them have said they would withdraw from the New Zealand market.

To mitigate this risk, we have made a number of simplifications to the proposals, compared with the original proposals that were consulted on in the discussion document. Raising the proposed threshold to $1,000 is part of this simplification.

Ultimately it is hard to be certain whether the marketplaces may comply, but the experience of Australia to date is encouraging.

Q29. The markets for cross-border services and for low-value imported goods are different. How relevant is the experience with GST on cross-border services for determining the likely level of compliance with an offshore supplier registration system for low-value imported goods?

Yes they are different markets, but the bottom line is that the suppliers are commercial enterprises in the business of selling their products around the world, and therefore an approach of non-registration or of refusing to sell goods to certain markets is unlikely to be sustainable as more countries adopt similar rules.

So, while the greatest concern with an offshore supplier registration system for low-value imported goods is the level of compliance with the rules, the success of the rules for cross-border services both in New Zealand and other countries is an encouraging sign.

Q30. Some marketplaces and re-deliverers may not have all of the information necessary to correctly determine their GST liability. What should these marketplaces and re-deliverers do?

It is true that some marketplaces and re-deliverers may lack the necessary information to correctly determine their GST liability.

For example, a marketplace will need to know the residency status of its underlying suppliers to determine whether the marketplace is the deemed supplier of the goods sold by any particular supplier on its platform. A marketplace may lack the information to precisely determine the residency status of its underlying suppliers.

To address this issue, marketplaces and re-deliverers will be able to agree with the Commissioner of Inland Revenue on an appropriate method for determining their GST liability.

Marketplaces and re-deliverers that have agreed with the Commissioner would then be able to use the information they do have available to determine their GST liability.

If there is then a discrepancy between the actual amount of GST a marketplace or re-deliverer returns and the amount that should have been returned, the marketplace or re-deliverer will not be held liable for this on the basis that they have acted in good faith in using the method agreed with the Commissioner for determining their GST liability.

Q31. What happens if a marketplace does not process payments and is unable to collect the GST from the underlying supplier of the goods?

Marketplaces that do not process the payment for a supply of goods to a consumer in New Zealand would be entitled to a bad debt deduction if they are unable to collect the GST from the underlying supplier of the goods.

However, the marketplace would only be entitled to this deduction if they are also unable to collect any fees or commission the marketplace charges the underlying supplier in relation to the supply. The marketplace will also not be entitled to this deduction if they are associated with the underlying supplier of the goods.

COMPLIANCE

Q32. How would the Government enforce a requirement on offshore suppliers to register for and return GST if suppliers do not voluntarily comply?

We intend to make New Zealand’s rules as simple as possible for offshore suppliers to comply with. The experience with similar rules for imported services suggests making the rules as simple and easy to comply with as possible will encourage compliance.

However, it is acknowledged that there will be some suppliers that will not comply with the proposed rules. We will therefore be monitoring compliance and using a number of methods to detect non-compliance.

New Zealand has agreements with other countries on mutual co-operation, information exchange and assistance in tax matters. These agreements cover an extensive network of jurisdictions, including our major trading partners.

The agreements mean New Zealand can request that our treaty partners (that is, other foreign tax authorities) provide information about foreign taxpayers. In addition, Inland Revenue and Customs will share information and work together to help identify instances of non-compliance.

When non-compliance is detected Inland Revenue will register the supplier for GST and issue a default assessment of the GST liability. This debt would then be registered with the New Zealand courts.

Using our international agreements the debt would then be registered and pursued in the courts of the country that the supplier is based in. New Zealand also has agreements with some foreign tax authorities allowing them to collect unpaid GST on New Zealand’s behalf.

Alternatively, Inland Revenue could order persons based in New Zealand that owe money to non-compliant offshore suppliers to instead pay those funds to Inland Revenue.

Q33. Why would the Government expect offshore suppliers of low-value goods who have no physical presence in New Zealand to voluntarily comply with a requirement to collect and return New Zealand GST?

Where similar rules have been applied in other countries to tax cross-border services and intangibles, offshore suppliers have demonstrated a willingness to comply.

This has been the experience in New Zealand so far with the new GST rules for cross-border services and intangibles, under which over 200 offshore suppliers have registered to date.

The number of registrations in Australia is also an encouraging sign that offshore suppliers would be prepared to comply and pay their fair share of GST on goods consumed in New Zealand.

Q34. The Australian Treasury estimated that Australia’s new legislation would only collect twenty five percent of the potential GST revenue on low-value imported goods, why would New Zealand be any different?

The twenty five percent collection rate estimated by the Australian Treasury is a conservative assumption for the first three years of Australia’s legislation. Australia’s collection rate is estimated to increase to fifty four percent at maturity.

Note however that Australia’s collection rate represents the proportion of GST they expect to collect out of the estimated total gross GST revenue that would be collectable on low-value goods imported into Australia, including business-to-business supplies and supplies made by businesses below the registration threshold.

Analysis by the Australian Productivity Commission suggests that excluding suppliers below the registration threshold (other than those selling through marketplaces) increases the maximum potential collection rate to somewhere between fifty one and seventy eight percent.

Presumably excluding business-to-business supplies from the denominator would increase these maximum potential collection rates even further. In contrast the figure of seventy five percent used in New Zealand already excludes suppliers below the registration threshold and business-to-business supplies.

The New Zealand and Australian estimates are therefore comparable once the differences in how they are calculated are taken into account.

Q35. Isn’t it unfair on those suppliers and marketplaces that do comply if other suppliers do not comply?

Yes. That is why we will be working hard to enforce compliance from non-compliant suppliers.

Q36. Can you provide an update on the GST and cross-border services rules, for instance, how much GST revenue has been returned by offshore suppliers of services and intangibles so far?

Over 200 offshore suppliers have registered for GST under the new cross-border services rules.

The total GST revenue returned by offshore suppliers in the 2017/18 tax year (1 April 2017 to 31 March 2018) was $131 million. This is a significant increase on the $40 million that officials initially forecast would be brought in by the rules in their first 12 months.

Source: Deloitte New Zealand, Inland Revenue

P.S. We’d love to answer any of your questions! Contact us now . Do you know of other people that will find this article useful? Please share it on social media. Thank you!