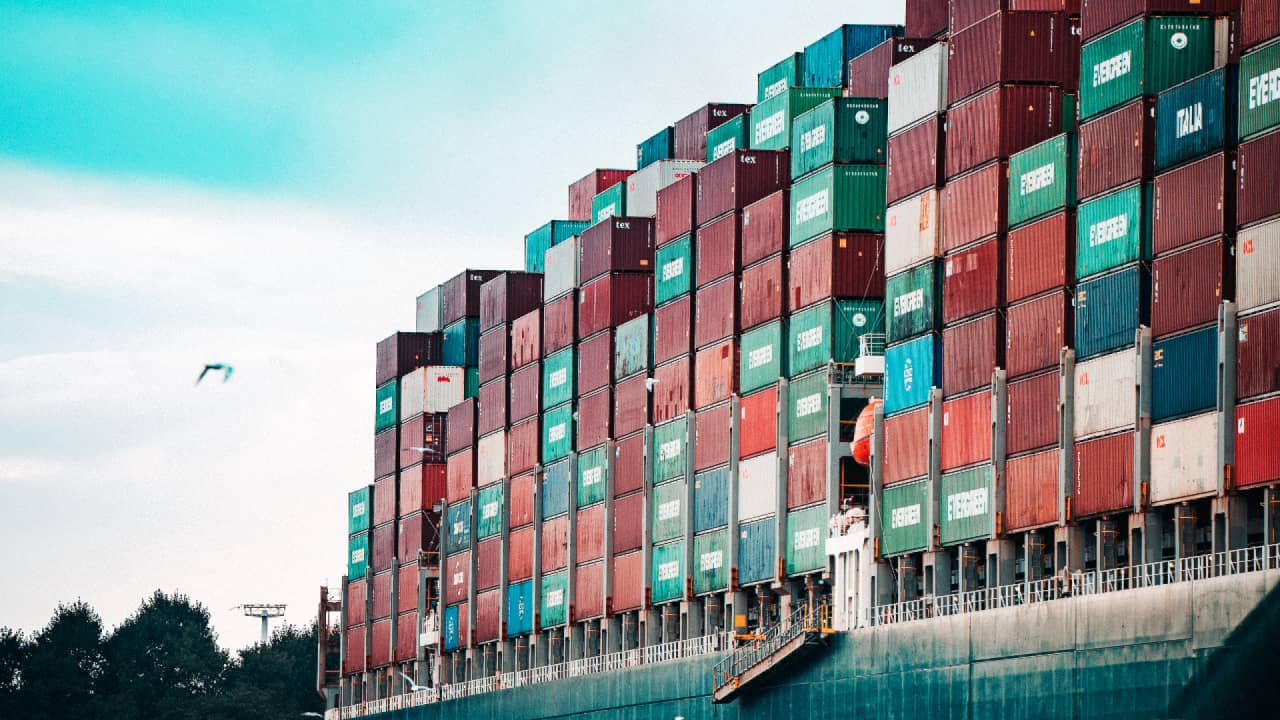

Increase in Containers Lost Overboard Sees Industry Take Action

5-minute read

The latest loss of containers from the APL Vanda has once again thrown the spotlight on the problem of boxes being lost at sea and what can be done to prevent it.

The CMA CGM vessel suffered a stack collapse that saw 55 containers lost overboard from a single bay in heavy weather en route from Singapore to Suez, just before entry to the Gulf of Aden. No injury was reported.

The 17,300-TEU ship docked in Djibouti to clear some damaged containers on deck before continuing her voyage. That would have been of relief to shippers with cargo onboard who got stuck into CMA CGM for delays in informing them of the arrangements for discharging boxes.

Those with cargo inside the 55 boxes did, of course, not have anything discharged. For them, insurance claims lie in the offing.

The question arises as to how this accident occurred. Discussion so far has concentrated on monsoon winds blowing from the equator to the Indian Sub-Continent, which gave rise to heavy swells.

Those swells on the ship’s port bow to port beam may have led to synchronous rolling and container loss on the starboard side.

Synchronous rolling of ships involves waves coming onto the ship’s beam and quarter, which synchronise with the ship’s natural roll period. The two can combine to result in violent rolling motions.

Parametric rolling tends to affect vessels such as containerships with a large bow and stern flares.

Larger waves with a length equal to the ship’s length, and a wave period that is half the ship’s natural roll period, can quickly trigger violent rolling, which in turn can put extreme loads on container lashing and securing gear.

The worrying thing is that the monsoon season happens every year, so it’s not as if vessels moving through the approaches to Suez are striking something new, yet here we have a large boxship losing boxes over the side.

Last year, this became a topic for the mainstream media in New Zealand after several major international incidents within a few months.

The ONE Apus lost about 1800 boxes overboard in the Pacific en route to Long Beach.

Just prior, the ONE Aquila also suffered a container loss in the North Pacific, which was thought to be over 100, followed by the loss of 36 containers from Evergreen’s Ever Liberal.

Then came another biggie: the Maersk Essen lost about 750 containers en route to Los Angeles from China.

The World Shipping Council (WSC) recently published its Containers Lost at Sea Report 2022, which observed a “worrying break” in the previous downward trend for container losses at sea.

Almost 4000 containers were lost in 2020, and over 2000 boxes were lost in 2021.

Those were the second and third worst years in the history of the survey, which has been conducted on a three-yearly basis since 2008, except 2013 when the MOL Comfort sank with 4293 containers and the M/V Rena sank here in 2011, resulting in approximately 900 containers lost.

In other years, losses peaked at around 1500 or dipped below 1000. A three-year average annual loss trend of 779 containers was reported in 2019.

In 2021, international liner carriers managed 6300 ships, delivering about 241 million containers. Overboard losses represented less than one-thousandth of 1% (0.001%) that year.

While these latest increased losses are just a tiny fraction of the amount of cargo carried in boxes worldwide, the WSC accepts that “every lost container overboard is one too many”.

James Hookham, director at the Global Shippers’ Forum (GSF), told The Loadstar:

“Every box not delivered has a disappointed customer and consignee, and importantly it means there is freight either washing up on beaches or becoming a danger to shipping”.

So why are we getting these losses?

The WSC is stressing that efforts are being made to find the reasons and to increase safety further. Stakeholders across the supply chain have initiated the MARIN Top Tier project to enhance container safety, of which WSC and member lines are founding partners.

The project will run over three years and will use scientific analyses, studies and desktop modelling as well as real-life measurements and data collection to develop and publish specific, actionable recommendations to reduce the risk of containers being lost overboard.

Initial results from the study show that parametric rolling in following seas is especially hazardous for container vessels, a phenomenon that can develop unexpectedly with severe consequences.

Research suggests that larger, stiffer container vessels tend to have shorter natural roll periods that more closely match common wave periods.

A contributing factor to box losses is that ships are getting larger; therefore, stack heights are greater, and the forces at play on the lashings and securing gear are greater when the ship hits difficult weather conditions.

Today’s largest container ships have a capacity of just under 24,000 TEU, with a length of 400 metres and a beam of over 60 metres, making the ships more stable at the expense of making them stiffer.

Almost all container stack collapses at sea occur in rough weather with strong winds. The deck stacks present high windage areas that, combined with large freeboards, act like giant sails to amplify a ship’s motions as the weather deteriorates.

With container stacks experiencing lateral and vertical forces, if one stack goes, it can destabilise the stack next to it.

Other factors come into play to impact the ship’s stack stability. The distribution of weights is one whereby generally, deck containers are stacked in weight order, with the heaviest at the bottom tier and the lightest at the top to minimise loads on the lashing and securing.

This relies on accurate knowledge of container weights, and calculations can be skewed if mis-declared or overweight containers are inadvertently loaded into the upper tiers.

That is why the International Maritime Organization (IMO) amended SOLAS chapter VI in 2016 to require mandatory verification of the gross mass of packed containers loaded on ships.

Incorrect packing of containers can lead to instability if contents shift. This remains an issue because masters and officers do not have sight of or control over the contents of containers or the methods by which they are packed and secured.

The IMO, the International Labour Organization (ILO) and the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) approved a Code of Practice for the Packing of Cargo Transport Units (CTU Code) in 2014 to help the container industry ensure the safe stowage of cargo in containers.

Then there is the physical condition of the lashing equipment, the correct application of that equipment and the physical condition of the containers.

These factors affect all container vessels, irrespective of the size.

The WSC is endeavouring to take further preventative action. A Notice to Mariners has been developed, describing how container vessel crew and operational staff can plan, recognise and act to prevent parametric rolling in following seas.

Additionally, the WSC and member companies are actively contributing to the revision of IMO guidelines for inspection of cargo transport units and support the creation of a mandatory reporting framework for all containers lost overboard.

While the lost freight can be estimated, the clean-up and environmental costs cannot, and considerations of the environmental damage must be taken into account, and the WSC’s move to increase carrier surveys on container losses to annual events rather than tri-annual surveys was welcomed by the industry.

Source: The New Zealand Shipping Gazette and The Loadstar

P.S. Easy Freight Ltd helps New Zealand importers & exporters to save money on international freight and reduce mistakes by guiding how to comply with Customs and biosecurity rules.

➔ Contact us now to learn how we can assist you.