How to Decide if You Need Cargo Insurance & Who Pays for It?

6-minute read

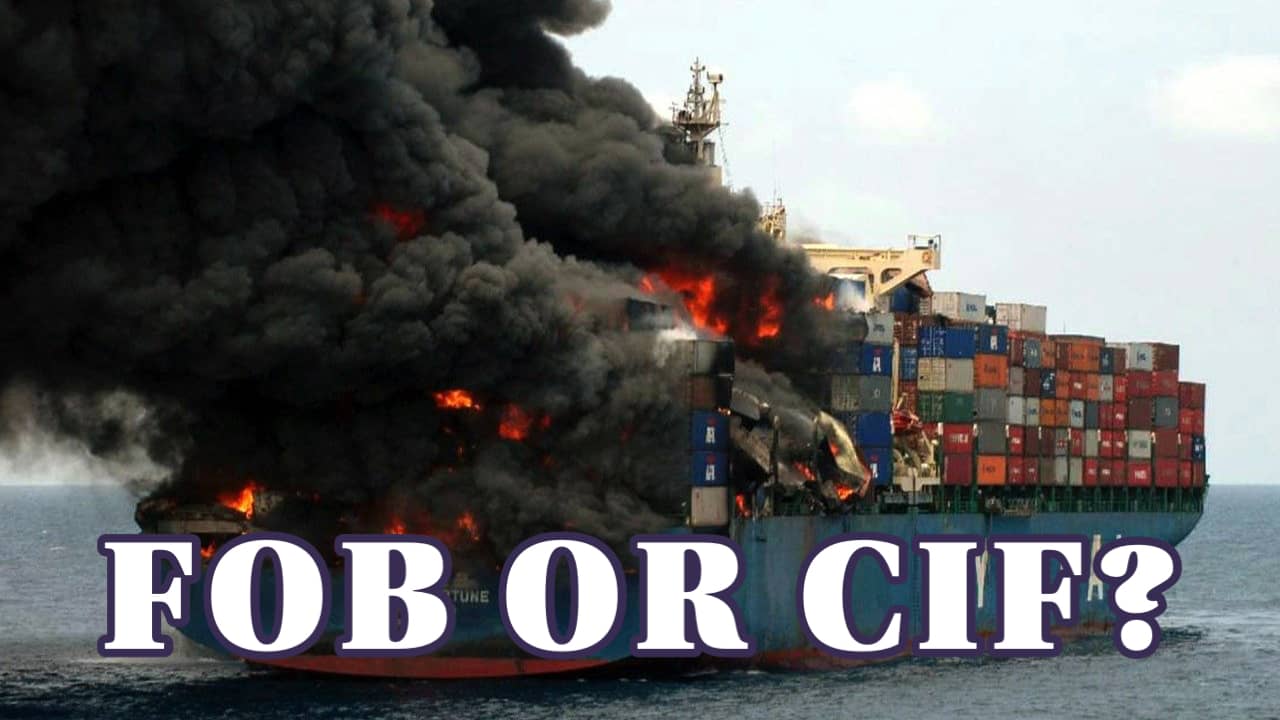

One of the examples of how “General Average” works was Maersk’s declaration of it following the fire on board the Honam. It caused some interesting feedback relating to the value of having marine cargo insurance.

In particular, the issue that was drawn into sharp focus was the risk borne by all New Zealand exporters and importers, who proceed to ship goods without marine insurance.

It takes a major incident such as the Maersk Honam or the Rena for the importance of insurance to become a high priority for many smaller shippers.

In truth, that’s true for most of our insurance cover — we tend to view it as a bit of a burden, thinking the chances of us needing to use it are low and are only thankful of it when something untoward happens.

But smaller shippers, who don’t have the support of shipping departments to handle their transactions, may rely on coverage contained in carriers’ bills of lading, or freight forwarders’ bills of lading, or truckers’ liability under the Carriage of Goods Act, and unwittingly be putting themselves at significant risk.

An indication of how insured and uninsured shippers fare differently when mishaps occur was highlighted in the Maersk Honam article.

Under General Average, all the parties to the voyage must contribute to cover the losses involved when cargo is voluntarily sacrificed to save the ship, crew or the remaining cargo.

They even have to stump up straight away with cash or guarantees, to assure the General Adjuster they will pay whatever is deemed to be the final cost.

In the case of Maersk Honam, General Adjuster Richards Hogg Lindley advised cargo owners they must sign a bond.

If the cargo is insured, the insurers can sign a guarantee. For uninsured cargo, however, a cash deposit is required from the shipper.

There were no reports of any New Zealand cargo on the Maersk Honam but with relay services now a backbone of our bluewater trades, there is a chance of our goods being on any Asia-European service.

The Rena prompted a surge of interest in insurance from exporters and importers due to this being a ship in New Zealand waters on a New Zealand service, carrying New Zealand cargo.

Perhaps the Maersk Honam triggered a new wave of interest so let’s traverse some of the main points about why marine cargo insurance should be a consideration for both exporters and importers.

First, what is “marine” cargo insurance?

It will generally cover goods from the time and place of acceptance by the carrier up to the time and place of delivery by the carrier at the final destination, and cover the rail and truck moves at either end.

Normal stoppages such as relay transhipments, ship delays and the like will normally be covered, and General Average (and salvage expenses) should also be covered.

So why should NZ shippers and importers consider getting insurance cover , rather than relying on the liability coverage of the shipping line, the freight forwarder, or even the insurance coverage arranged by the overseas buyer or seller?

Shipping lines, freight forwarders and road and rail operators all carry limited liability. These will be found in their contracts, terms of trade, waybills, or bills of lading.

However, in the event of a claim, the liability – as the term suggests – will be limited.

Compensation may not cover more than a small percentage of the value of the goods lost or damaged.

So any shipper or importer relying purely on these provisions is taking a risk unless additional insurance cover is arranged.

Even if it is, there is still risk to be considered if the insurance is arranged by the offshore party (the seller in the case of an NZ importer, and the buyer in the case of an NZ exporter).

The insurance terms settled upon will be out of the control of the NZ importer or exporter — unless that importer or exporter makes it their business to specifically check them and agree to them.

And then there’s a third element of risk. Even if the insurance is arranged by the offshore party, and even if the NZ importer or exporter agrees to the terms, any dispute or legal action arising in the event of a claim is liable to be dealt with in a foreign court.

Let’s start with the example of an importer. Many importers may buy their goods under CIF terms (cost, insurance and freight) or something similar.

In other words, it’s up to the seller at the other end to organise not just the supply of the goods being purchased but also the shipping arrangements, pay for the freight and organise the insurance.

When it works well, that’s a nice package deal.

But insurance only comes into play when things go wrong, and it’s when things go wrong when complications can arise.

Is the importer aware of the insurance terms negotiated by the seller? Do those terms cover the importer adequately for the loss?

All the insurance arrangements, and the insurance firms involved, will probably be based offshore, possibly speaking other language and probably in another time zone.

It will be up to the seller of the goods, as the party entering the insurance contract, to sort out any claims.

The importer is therefore at the behest of his/her overseas customer as to how fervently the claims are pursued.

If the deal has already been done, and the seller paid in advance, the seller certainly won’t have the same motivation as the importer to get a claim settled.

The alternative is for the importer to do the deal on FOB terms (free on board). Sure, the importer is lumped with the task of arranging the freight and insurance, but also gets to negotiate the insurance terms with an insurance provider in New Zealand.

It’s not a clear-cut decision which pathway should be chosen, CIF or FOB . It’s up to the importer to decide his or her level of risk.

But either way, the importer needs to be assured that dependable insurance arrangements are in place.

As for exporters, they too may be exposed if they allow the overseas customer to arrange marine cargo insurance.

Sales terms such as ex-works (EXW), FOB or cost and freight (CFR) take the onus of organising insurance cover out of the hands of the exporter and hand it to the buyer.

Unless the exporter has been paid upfront, the exporter is relying on the buyer to arrange adequate cover for goods which not have been paid for.

If the goods arrive damaged, or if the goods or shipping documents are rejected at arrival, or if the buyer’s insurance does not cover the loss, the exporter may end up being out of pocket.

With FOB export sales, exporters may also overlook arranging adequate insurance for the transport sector from their premises to the port.

For some high-value cargo, we insist on the shipper taking out insurance.

While freight forwarders would have limited liability to protect its own interests, the company does not want to run the risk of being a party to a messy claim nor does it want to see its clients taking a gamble with a container of goods that may be worth six figures.

As said earlier, it’s a question for smaller shippers of calculating risk. But as the Rena and Maersk Honam cases underline, peace of mind may be found in giving marine cargo insurance a second thought.

Source: Shipping Gazette

We’d love to answer any of your questions! Contact us now

P.S. Do you know of other people that will find this article useful? Please share it on social media. Thank you!